Detraining (DT) is the notion of taking a rest away from exercise for the purposes of recovery before retraining again. Deloading (DL) is the idea of reducing the training load whilst maintaining some level of training. The purpose of this article is to explore the changes undergone when resistance training, the damage exercise induces to muscles and the recovery period needed from that, what happens during a DT and DL phase and how to suitably prescribe DT/DL to an athlete.

You can click on the headings below to jump to that part of the article:

- How the body adapts to resistance training

- How the body is affected by a detraining phase

- Optimum detraining

- Practical applications

- Reference list

How the body adapts to resistance training

During early phases of resistance training, such as those experienced by people who have never undergone resistance training before, 60% of the changes to strength are from changes to the neural drive and possibly muscle architecture (27). This has since been proven by increases in Electromyography (EMG) signal amplitude (1) and rate of EMG rise in early phase of muscle contraction after 10 and 14 weeks of training.

This is particularly relevant to females who show strength improvements due to factors other than muscle mass changes (14). Female strength training can elicit slower hypertrophy responses in upper body compound exercises, such as the bench press, in the first 10 weeks of resistance training (5. 7).

Strength development is a blend of neural and physiological changes. These changes could also affect the genders differently which will be key to effective programming and deload training.

Physiological changes to strength training include (9):

- An increase in cross-sectional area (CSA) of the whole muscle (32)

- An increase in individual muscle fibres due to an increase in myofibrillar size and number

- Satellite cells are activated in the early stages of training then later fuse with existing fibres which appears to be associated with the hypertrophy response

- Changes in muscle fibre type increasing the 11a and 11ab (34)

- Changes in muscle fibre length

- Changes in pennation angle

- Changes in myofilament density

- Increases in muscle tendon CSA and stiffness after 2 months of resistance training (19)

How the body is affected during a detraining phase

During a DT phase, strength decreases have been reported from between 6 to 9% following a 4 week total exercise abstinence for both lower and upper body (15). Whereas power decreases can be as much as 14 to 17% (15. 18) with anaerobic changes returning to base line after 4 months of exercise cessation (8).

One of the main physiological changes when developing strength is in the ratio of muscle fibre (MF) type, viz. increases in IIa and IIab with decreases in IIb (9. 34). A DT phase for longer than a 4 week period will see an increase in the IIb muscle fibres and decreases in IIa and IIab (34) which will have a negative impact on strength and be partly responsible for the reported decreases in strength above.

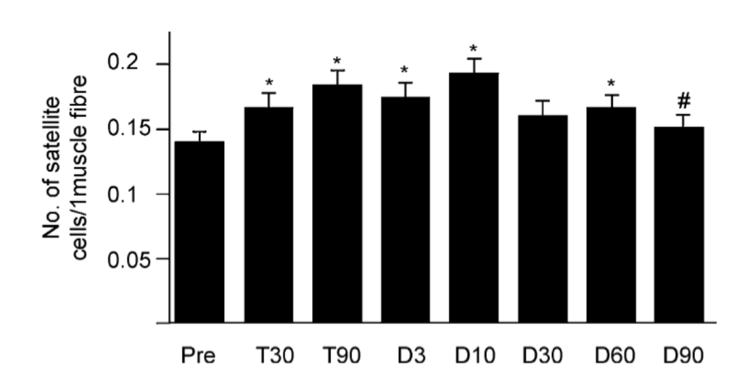

Satelitte cells are normally dormant cells, found only in adult muscle, and serve as a reserve set of cells (25). These reserve cells are able to proliferate in response to injury and give rise to regenerated muscle and to more satellite cells. This proliferation is experienced during initial phases of strength training. This is the cause for MF length increases (25) which has been associated with the changes experienced during strength training (17). Changes to satellite cell count can increase by as much as 31% after 90 days of training. DT for up to 10 days can continue this increase in satellite cells (figure 1) after which they will slowly decline to pre-training levels after 90 days of detraining (16).

The changes to MF type after DT have been reported to take as long as 12 weeks to take effect (13). This indicates neural adaptations and changes are integral to the changes experienced over shorter periods. A decline in neural activation has been shown after a 6 week DT phase (33) although will remain above baseline for as long in 31 weeks (14). Thus highlighting the faster rate of change for the neuromuscular system than for those within the muscle structure.

Changes to the elongation and stiffness of muscle tendons during resistance training take longer than neural and strength adaptations by up to 2 months (19). However, post training rest periods show the tendons also take longer to return to baseline. Reported stiffness starting at 19.4 N/mm pre-training changed to 37.2 N/mm after 3 months of resistance training then adapted to 32N/mm after 1 month of DT. Similarly, the elongation of the tendon reduced from 5.3mm pre-training to 3.6mm after 3 months of resistance training and returned to 5.4mm after one month of DT (19). The effect of DT on tendon stiffness and CSA changes will be detrimental if a sustained period of DT is taken, longer than 4 weeks (20).

Exercise induced muscle damage (EIMD) can have many different effects on performance, viz. delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) (2. 4. 21), reduced strength (10) and a smaller range of motion (ROM) (31).

If EIMD continues to have these impacts on training a slow decline in strength improvements could be experienced. Although exercise on damaged muscles will not increase the damage seen and will not decrease the rate of recovery, it will impede muscular adaptation (28. 29).

The predominant amount of damage is seen in type IIa and IIab MF types and have shown to cause the longest duration of muscle damage preventing adaptations (3). However, this is seen less so in young men due to their lower rate of these MF types and nautrally being more flexible (22). This is why it is so important for strength athletes to take a period of recovery as the MF types they are trying to increase are those that require the longest duration for damage recovery.

How to optimise a recovery period

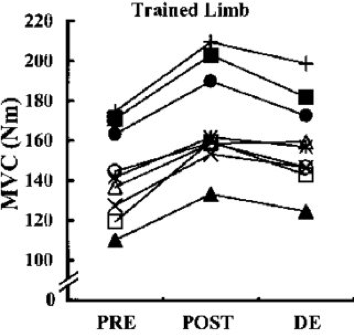

Strength can maintain for up to 4 weeks of a complete exercise abstinence, termed here a DT phase, and is most affected following this from 5 to 16 weeks in moderately trained populations (23). For highly trained athletes strength values start declining after 3 weeks (24. 26). This period of strength maintenance is because the physiological and neurological changes have not begun to negatively affect the muscles performance (26).

The duration of a DT is as important as period of time to retraining and strength testing. 16 weeks of DT has been shown to significantly affect strength (23). With only an 8-week retraining period strength values remained the same after the initial 12 week training phase (31), although this was tested on an older population. A 16 week DT phase, as seen from Marques (23), will induce significant strength decreases anyway. Allowing for a small DT phase such as the recommended 3 weeks (24. 26) would minimise the any negative physical changes and mean a successful and fast retraining phase should ensue.

Practical applications

It has been reported that resistance trained people can be split in to three groups; high >15%, medium 15-5%, low responders <5% (30). Those who responded quickly to hypertrophy improvements, high responders, reduced in their developments quicker (-9.3%±5.7 for muscle CSA and -2.1±3.1% for 1RM) than low responders during a 6-week DT (-0.5±8.4% for muscle CSA and +0.1.9±3.4 for 1RM).

Previous research indicates a 4-week reduction in training volume (repetitions multiplied by sets), termed here a DL, whilst keeping intensity high (percent of 1RM) saw an increase in muscular strength of 2% although no change in power output (15).

Therefore, providing an athlete with a complete exercise cessation for between 7 to 10 days (DT), and no longer than 3 weeks, will ensure satellite cell levels are raised, neurological adaptations have not yet started to change and will mitigate any declines in strength meaning a more advantageous starting point for the retraining phase. Providing the athlete with a DL by reducing volume but maintaining intensity for 4-weeks may maintain or continue to improve strength development. However, this may not have the desired recovery effect on other physiological factors such as muscular damage recovery and tendon recovery. Furthermore, retraining for 6 weeks can return the athlete back to training status with an additional 7 weeks continuing the improvements above previous training phase (34).