Power development as long been a focus from coaches and athletes for sports performance improvements and has had much attention within the research. However, the challenge for the coach has been to understand what type of power is needed for their sport and how to enhance it. This article aims to provide a guide of the literature for power development.

Power is the resultant force production exerted from the body at a given velocity (9) utilising the triple extension at the hip, knee and ankle for lower body development. Power has been broken down in to 6 qualities of athletic performance (16):

- Speed strength

- High load strength (HLSS)

- Low load speed strength (LLSS)

- Rate of force development

- Reactive strength

- Skill performance

- High load strength (HLSS)

This article will be focusing on the development of high load and low load speed strength and the exercises suitable for these skills.

High load speed strength

HLSS focuses on the body’s ability to overcome a large load, >30% of the person’s 1 repetition maximum (1RM) (16). Development of this often uses loaded exercises such as Olympic Weightlifting (WL) derivatives and movements such as the Jump Squat (JS). This is because the movements mimic the acceleration and triple extension of the lower body with no deceleration, which other types of strength training exercises do not (9).

HLSS training has been shown to improve jump performance (3. 18) and produce similar characteristics to a non-countermovement jump for maximal power, time to maximal power and relative power (3). This has been related to sprint performance (9. 24) however has not shown any correlation to change of direction or agility (9). Therefore, following an analysis of the biochemical requirements of the sport, high level athlete performances and pre/post test results of the subject (16) if a requirement of HLSS is assessed the following exercises may be prudent to implement for the purposes of peak power (PP) development.

WL derivatives have shown greatest peak power production (PP) at loads of between 70 and 80% 1RM (Soriano, 2015) and the details of these are laid out in the table below (table 1).

| Exercise | PP output (Watts) | %1RM | Reference |

| Hang power clean | 4466 ± 477 | 80 | Kilduff et al, 2007 |

| Power clean | 4786.63 ± 835.91 | 80 | Cormie et al, 2007 |

| Hang power clean | 70 | Kipp et al, 2018 | |

| Hang clean | 4123.61 ± 1134.32 | Suchomel, Wright, Kernozek, Kline, 2014 | |

| High pull | 4737.08 ± 1196.36 | 45 of hang clean | Suchomel, Wright, Kernozek, Kline, 2014 |

Table 1: A table depicting the Olympic Weightlifting derivative exercises, their power output, the percent of 1 repetition max this was achieved and the research article this data was extracted from.

Although it seems WL derivatives are ideal for the development of HLSS issues have been faced in implementing these training strategies particularly as they are very technical movements and take a lot of hours to learn. This may not be ideal for a team of athletes such as a football team who have limited time with the Strength and Conditioning (S&C) coach.

An easier exercise to implement that still allows for loading and focuses on the explosive nature of muscles is the Jump Squat (JS). This exercise sees the athlete jumping as high as possible with a loaded bar across their shoulders. Typical loads for PP output have been shown to be between 0-30%1RM (22) and can be seen in the table below (table 2).

| Exercise | PP output (Watts) | %1RM | Reference |

| JS | 6437.14 ± 1046.34 | 0 | Cormie et al, 2007 |

| JS | 30-50 | Kipp et al, 2018 | |

| JS | 5851.38 ± 1354.94 | 30 of hang clean | Suchomel, Wright, Kernozek, Kline, 2014 |

Table 2: A table depicting power output of the Jump Squat exercise, the percent of 1 reptition maximum this was achieved and the literature this was extrapolated from.

Low Load Speed Strength

LLSS has been shown to enhance power output similar to WL (1. 6) but utilises Plyometric exercises such as jumping, hoping and bounding. These can be easier to implement, particularly on a large group of athletes or an inexperienced population such as youth groups. Plyometrics focuses on utilising the Stretch Shortening Cycle (SSC) of the muscle and are generally performed unloaded or <30%1RM (9).

Plyometric training can improve agility speed (15), reduce sprint times (20) and vertical jump (VJ) PP output (19). These characteristics are seen in many sports such as football, basketball, athletics, tennis and racket sports to name but a few. Plometric training has also shown to produce the greatest developments when a mixture of Plyometric exercises are used (5).

There is limited data on the PP output from plyometric exercises, however the improvements in VJ PP output are from 15.4% (8660 ± 546.5W to 8793.6 ± 541.4W) following a 4 week Plyometric based training program (13), 26.2% (8702.8 ± 527.4W to 8729.6 ± 598.4W) after a 7 week program (13) and 29% (8335 ± 179 W to 8579 ± 174W) following an 8 week training program (19) on a physically active population. A lower reading of 17.7% (2723.04W to 3206.16W) has been shown on an untrained population after a 6 week training program.

As the reports show the PP output is greater in trained populations. This is because power is a product of force multiplied by distance divided by time (17) thus the greatest power is produced by the largest distance covered in the smallest time as a result of the largest force propelling it. When a load is added to the exercise, the amount of force required to move the object increases meaning the time to cover the distance required also increases thus reducing the power output.

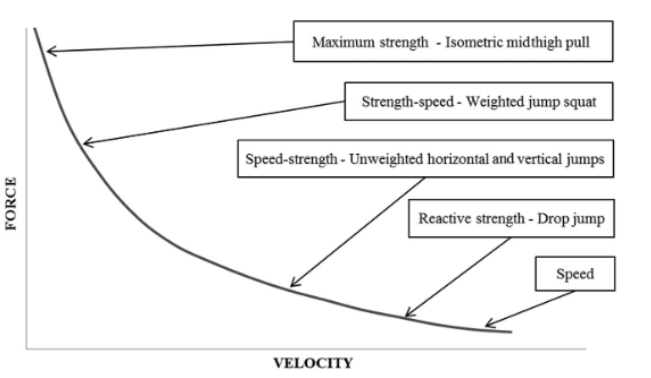

Figure 1: Standard model of the Force Velocity curve with examples of movements relative to each section of the curve (Brady et al, 2017)

It is essential to many sports to develop the force development characteristics of the athlete, however, that is a vast subject outside of the remit of this article. When a sport requires PP, utilising HLSS and LLSS can improve PP output values above that of heavy resistance strength training (17) which can be seen using the force velocity curve (Figure 1). Using HLSS will develop power on a different profile to that of LLSS.

When developing training programs to improve speed strength, typical repetitions per sets are five or lower. Certain sports such as a blocker in American Football may require power production under a fatigued condition in which the rest periods of sets can be reduced to improve specificity of the training variable (9). Equally, when looking for a broader improvement in athletic performance, WL training has shown to produce these to a greater extent than Plyometrics in physically active subjects (24).

Understanding the demands of the sport, high achieving athletes characteristics and the athletes current testing profile will provide the S&C coach with the minimum data needed to understand what elements of power are required to improve performance. The information above can support how to improve performance through the utilisation of HLSS or LLS and, thus, what exercises can be most beneficial to these characteristics.